Monthly Archives: December 2013

Review of Things Fall Apart

At sixteen, I read Chinua Achebe’s Anthills of the Savannah, a novel about the rise and fall of dictatorships in modern Africa. It was compelling, insightful, beautiful, and dense. This foray into non-Western literature was for me a glimpse of an alien world, one so foreign from the tradition of American and British writing in its senses of place, detail, character. I could go on, but suffice it to say that Achebe offered to me such powerful words that depicted the chaos of a continent rent asunder by totalitarian regimes and Western imperialism.

When I heard earlier this year the Achebe had passed away, I felt compelled to revisit his work before it came time to do the end-of-the-year post for Ambidexteri. I wanted to do something to commemorate his accomplishments while demonstrating an appreciation for one of his greatest novels: Things Fall Apart.

As Achebe first introduced the main character of Okonkwo, I felt instantly immersed in a way somewhat reminiscent of The Good Earth–the world was genuine, the language simple and sincere. The novel follows Okonkwo from the life of his slothful father to the growth of his own children. Achebe builds Okonkwo from several angles, and this makes him a compelling character, if not relate-able. The impact his father’s poor nurturing has on his values and identity evokes a strong sense of empathy for him as he starts his underprivileged life. Okonkwo’s determination and accomplishments despite the setbacks of his unfortunate upbringing and consistent run of bad luck make him admirable. His tenderness and compassion contrast with his strictness and temper, making him a conflicted but very human persona. While I would not say I always like Okonkwo or his behavior, he consistently remains the protagonist. This certainly speaks to Achebe’s aptitude as he creates not a heroic but rather an exceptionally real character.

What made the whole of this piece so compelling was not Okonkwo, however. Umuofia, the village in which Okonkwo and his family live, is Achebe’s medium for depicting Africa before and after Western religious, political, and cultural imperialism. Like Okonkwo, the village is not perfect–there are conflicts between members of the clan and with other clans. Achebe uses Okonkwo and his experiences to highlight various elements of Nigerian ethnic identity, such as anamism and the role that this faith plays in personal life, which in turn emphasizes the importance of family. Indeed, all aspects of their culture are interconnected like strands of a spider’s web: sever one strand, and the whole falls apart. Achebe’s beautiful depiction of this highly-evolved society becomes stark as missionaries, and later political administrations, begin to wear at its fabric.

What I found most intriguing in the end, with Okonkwo’s ultimate response to the white man’s new place in Umuofia, is the way in which Okonkwo and his life reflect almost as microcosm the life of Nigerian society. The grief and pain he suffers at the hand of the District Commissioner is symbolic of the early throes of death his village begins to show in its complacency and fatigue. Achebe’s final depiction of Western imperialism is done not through Okonkwo or the disintegrating clan, but rather through the head of the white man’s political administration: The District Commissioner. This overseer himself fancies writing about the life of Okonkwo in “[p]erhaps not a whole chapter but a reasonable paragraph, at any rate,” ending with an alternative title to Achebe’s novel: “The Pacification of the Primitive Tribe of the Lower Niger“. Particularly heart-rending is this suggestion that the end of a culture and civilization should be considered modernization, or even an act of kindness.

Compelling and insightful, Achebe’s Things Fall Apart is brilliant, eloquent, and riveting. His simple language, complex characters, and detailed world make for a moving read about the dramatic changes experienced in Nigeria during the European conquest.

Some favorite quotations:

“A man could not rise beyond the destiny of his chi. The saying of the elders was not true–that if a man said yea his chi also affirmed. Here was a man whose chi said nay despite his own affirmation.”

“Your mother is there to protect you… And that is why we say that mother is supreme. Is it right that you, Okonkwo, should bring to your mother a heavy face and refuse to be comforted? Be careful or you may displease the dead.”

“We do not pray to have more money but to have more kinsmen. We are better than animals because we have kinsmen.”

“The white man is very clever…. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.”

“He mourned for the clan, which he saw breaking up and falling apart…”

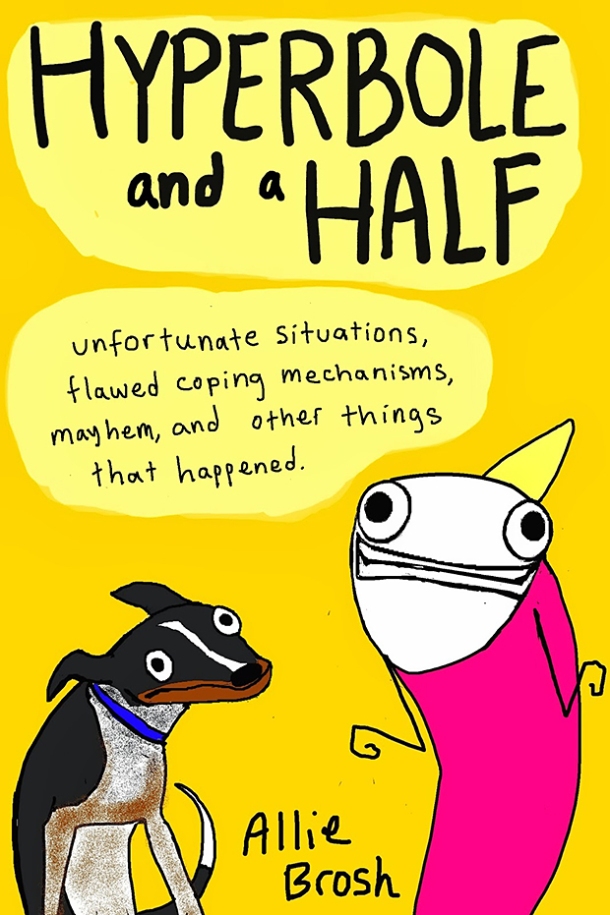

Review of Hyperbole and a Half

Allie Brosh’s hysterical blog, Hyperbole and a Half, has been one of my favorites for years. Her stories, comprised of carefully combined words and pictures, would bring me to tears, I would laugh so hard. Her book, subtitled Unfortunate Situations, flawed coping mechanisms, mayhem, and other things that happened, is no disappointment. While reading the book on a plane, I had to try my hardest not to disturb my seatmate.

Brosh’s book includes some classic stories from her blog, such as The Simple Dog (starring her probably mentally challenged canine), The God of Cake, and The Party (wherein little Allie begs her mother to let Allie attend a party while heavily sedated), and adds in a handful of never-before-read stories, which are just as side-achingly funny.

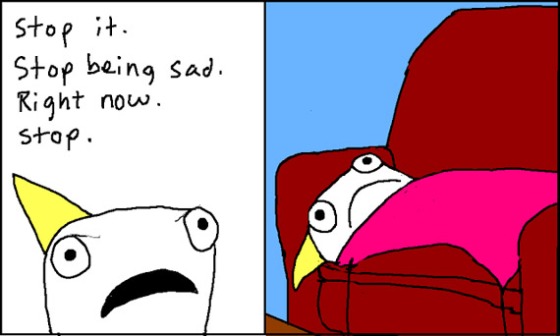

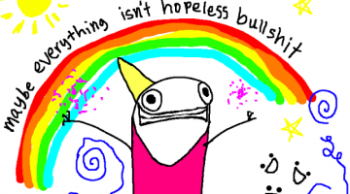

Then there are the more sobering stories. After regaling her large audience with funny tales for a few years, Brosh fell suddenly silent . There were no more new blog entries and this book, set to be published in September of 2012, didn’t appear on shelves that month. Everyone wondered where she went, and a few months later, she reappeared with a post entitled, Depression, Part 1, about her continued struggles with mental illness. While Brosh relayed her story with her usual comedic skill, there was a lot of startling, sobering, unfunny parts of this story. It was possible that Brosh’s audience would have shied away from this sudden change, but what happened instead was a reinforcement of dedicated fans’ support, and the gaining of a lot of new readers. Brosh’s book includes a continuation of the depression story, which explains that while she’s better. she’s still not cured, and probably never will be. Telling a different kind of story was a risk for Brosh, and one well worth taking.

I think the best part about Hyperbole and a Half is that it feels fresh when you’re reading it. Her new stories are devoured and her “old” stories are looked forward to eagerly. The book reads quickly and is a study on the (mostly) fantastic absurdity of life. I think I speak for all of Brosh’s fans when I say, Keep on keeping on, Allie.

Choice Quotes:

(It’s hard to capture Brosh’s greatest quotes, since many of them are in picture form. I’ll try, but buy her book, too.)

“Hey! What are you doing?”

“Playing a game.”

“What game?”

“‘What’s Wrong With Me?’ It’s like an Easter egg hunt for things that make me feel weird.”

…For a little while, I actually feel grown-up and responsible.I strut around with my head held high, looking the other responsible people in the eye with that knowing glance that says, I understand. I’m responsible now, too. Just look at my groceries.

I kept eating out of a combination of spite and stubbornness. No one could tell me not to eat and entire cake- not my mom, not Santa, not God- no one.